Scientists have discovered a way to use single missing atoms in crystals as memory cells, packing terabytes of data into a millimeter-sized cube.

By harnessing rare earth elements and light-based activation, they are creating a storage system unlike anything seen in classical computing.

Revolutionizing Storage: From Punch Cards to Atoms

From the punch card-driven looms of the 1800s to today’s smartphones, data storage has always relied on a simple principle: an object that can switch between “on” and “off” states can be used to store information.

In modern computers, binary code — ones and zeroes — takes different physical forms. In a laptop, transistors represent these states by operating at either high or low voltage. On a compact disc, a “one” appears where a tiny indented pit transitions to a flat surface, while a “zero” is a region with no change.

Traditionally, the physical size of these binary components has limited how much data a device can store. Now, researchers at the <span class="glossaryLink" aria-describedby="tt" data-cmtooltip="

” data-gt-translate-attributes=”[{"attribute":"data-cmtooltip", "format":"html"}]” tabindex=”0″ role=”link”>University of Chicago’s Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (UChicago PME) have developed a method to encode ones and zeroes using crystal defects — imperfections at the atomic level. This breakthrough could significantly enhance the storage capacity of classical computer memory.

Their findings were published on February 14 in Nanophotonics.

A Single Missing Atom Holds Memory

“Each memory cell is a single missing <span class="glossaryLink" aria-describedby="tt" data-cmtooltip="

” data-gt-translate-attributes=”[{"attribute":"data-cmtooltip", "format":"html"}]” tabindex=”0″ role=”link”>atom – a single defect,” said UChicago PME Asst. Prof. Tian Zhong. “Now you can pack terabytes of bits within a small cube of material that’s only a millimeter in size.”

The innovation is a true example of UChicago PME’s interdisciplinary research, using quantum techniques to revolutionize classical, non-quantum computers and turning research on radiation dosimeters – most commonly known as the devices that store how much radiation hospital workers absorb from X-ray machines – into groundbreaking microelectronic memory storage.

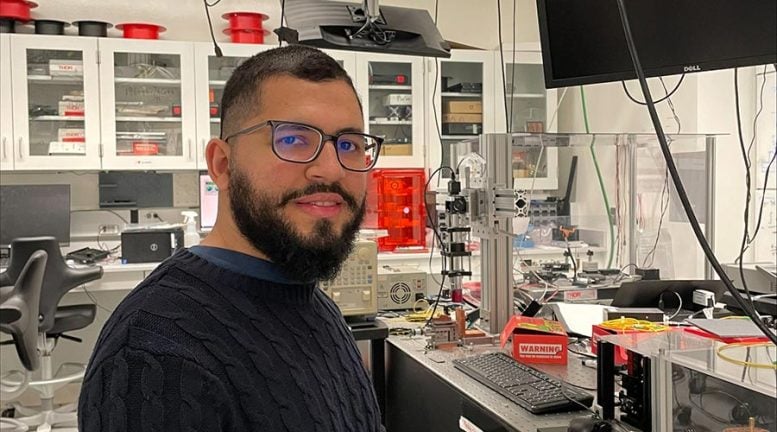

“We found a way to integrate solid-state physics applied to radiation dosimetry with a research group that works strongly in quantum, although our work is not exactly quantum,” said first author Leonardo França, a postdoctoral researcher in Zhong’s lab. “There is a demand for people who are doing research on quantum systems, but at the same time, there is a demand for improving the storage capacity of classical non-volatile memories. And it’s on this interface between quantum and optical data storage where our work is grounded.”

“Now you can pack terabytes of bits within a small cube of material that’s only a millimeter in size.”

Asst. Prof. Tian Zhong

From Radiation Dosimetry to Optical Storage

The research got its start during França’s PhD research at the University of São Paulo in Brazil. He was studying radiation dosimeters, the devices that store how much radiation workers in hospitals, synchrotrons and other radiation facilities receive on the job.

“In the hospitals and in particle accelerators, for instance, it’s needed to monitor how much of a radiation dose people are exposed to,” said França. “There are some materials that have this ability to absorb radiation and store that information for a certain amount of time.”

Harnessing Light to Store Data

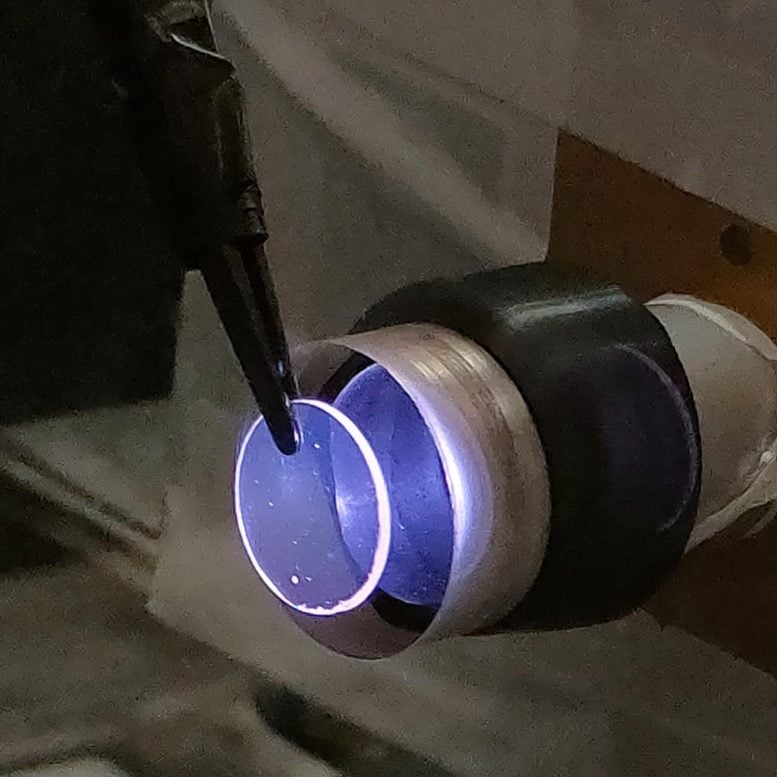

He soon became fascinated about how through optical techniques – shining a light – he could manipulate and “read” that information.

“When the crystal absorbs sufficient energy, it releases electrons and holes. And these charges are captured by the defects,” França said. “We can read that information. You can release the electrons, and we can read the information by optical means.”

França soon saw the potential for memory storage. He brought this non-quantum work into Zhong’s quantum laboratory to create an interdisciplinary innovation using quantum techniques to build classical memories.

“We’re creating a new type of microelectronic device, a quantum-inspired technology,” Zhong said.

Rare Earth Elements: The Key to Breakthrough Storage

To create the new memory storage technique, the team added ions of “rare earth,” a group of elements also known as lanthanides, to a crystal.

Specifically, they used a rare-earth element called Praseodymium and a Yttrium oxide crystal, but the process they reported could be used with a variety of materials, taking advantage of rare earths’ powerful, flexible optical properties.

“It’s well known that rare earths present specific electronic transitions that allow you to choose specific laser excitation wavelengths for optical control, from UV up to near-infrared regimes,” França said.

Trapping Electrons for Data Retention

Unlike dosimeters, which are typically activated by X-rays or gamma rays, the storage device is activated by a simple ultraviolet laser. The laser stimulates the lanthanides, which in turn release electrons. The electrons are trapped by some of the oxide crystal’s defects, for instance, the individual gaps in the structure where a single oxygen atom should be, but isn’t.

“It’s impossible to find crystals – in nature or artificial crystals – that don’t have defects,” França said. “So what we are doing is we are taking advantage of these defects.”

A Billion Bits in a Tiny Cube

While these crystal defects are often used in quantum research, entangled to create “qubits” in gems from stretched diamond to spinel, the UChicago PME team found another use. They were able to guide when defects were charged and when they weren’t. By designating a charged gap as “one” and an uncharged gap as “zero,” they were able to turn the crystal into a powerful memory storage device on a scale unseen in classical computing.

“Within that millimeter cube, we demonstrated there are about at least a billion of these memories – classical memories, traditional memories – based on atoms,” Zhong said.

Reference: “All-optical control of charge-trapping defects in rare-earth doped oxides” by Leonardo V. S. França, Shaan Doshi, Haitao Zhang and Tian Zhong, 14 February 2025, Nanophotonics.

DOI: 10.1515/nanoph-2024-0635

Funding: This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, for support of microelectronics research, under Contract No. DE-AC0206CH11357