A brain cap and smart algorithms may one day help paralyzed patients turn thought into movement—no surgery required.

People with spinal cord injuries often experience partial or complete loss of movement in their arms or legs. In many cases, the nerves in the limbs themselves still function, and the brain continues to produce normal signals. The problem is the injury to the spinal cord, which blocks communication between the brain and the rest of the body.

Researchers are now exploring ways to reconnect those signals without repairing the spinal cord itself.

Using Brain Scans to Capture Movement Intent

In a study published today (January 20) in APL Bioengineering by AIP Publishing, scientists from universities in Italy and Switzerland examined whether electroencephalography (EEG) could help link brain activity to limb movement. Their work focused on testing whether this noninvasive technology could read the brain’s movement signals and make them useful again.

When someone attempts to move a paralyzed limb, their brain still produces the same electrical patterns associated with that action. If these signals can be detected and interpreted, they could be sent to a spinal cord stimulator, which may then activate the nerves responsible for movement in that limb.

Why Avoid Brain Implants

Much of the earlier research in this field has relied on surgically implanted electrodes to read movement-related signals directly from the brain. Although those systems have shown promise, the researchers wanted to see if EEG could offer a safer alternative.

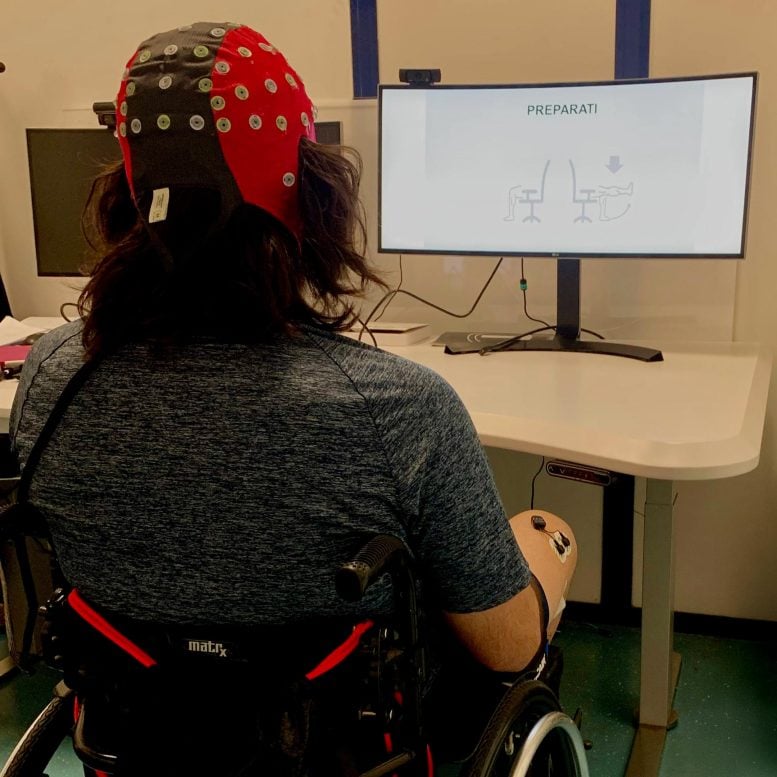

EEG systems are worn as caps fitted with multiple electrodes that record brain activity from the scalp. While they may appear complex or intimidating, the researchers argue that they are far less risky th an implanting hardware into the brain or spinal cord.

“It can cause infections; it’s another surgical procedure,” said author Laura Toni. “We were wondering whether that could be avoided.”

Limits of EEG Technology

Reading movement signals through EEG presents significant technical challenges. Because the electrodes sit on the surface of the head, they have difficulty detecting activity that originates deeper inside the brain. This limitation affects some movements more than others.

Signals related to arm and hand motion are easier to detect because they originate closer to the outer regions of the brain. Movements involving the legs and feet are harder to decode because those signals come from areas located deeper and closer to the center.

“The brain controls lower limb movements mainly in the central area, while upper limb movements are more on the outside,” said Toni. “It’s easier to have a spatial mapping of what you’re trying to decode compared to the lower limbs.”

Machine Learning Helps Decode Brain Signals

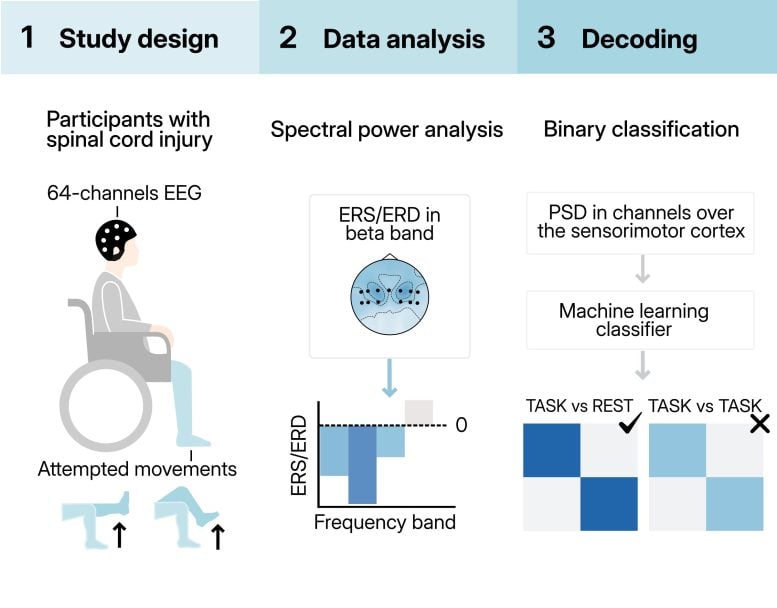

To make sense of the limited EEG data, the researchers used a machine learning algorithm designed to analyze small and complex datasets. During testing, patients wore EEG caps while attempting simple movements. The team recorded the brain activity produced during these efforts and trained the algorithm to sort and classify the signals.

The system was able to reliably tell when a person was trying to move versus when they were not. However, it struggled to distinguish between different types of movement attempts.

What Comes Next

The researchers believe their approach can be improved with further development. Future work will focus on refining the algorithm so it can identify specific actions such as standing, walking, or climbing. They also hope to explore how these decoded signals could be used to activate implanted stimulators in patients undergoing recovery.

If successful, this method could move noninvasive brain scanning closer to helping people with spinal cord injuries regain meaningful movement.

Reference: “Decoding lower-limb movement attempts from electro-encephalographic signals in spinal cord injury patients”by Laura Toni, Valeria De Seta, Luigi Albano, Daniele Emedoli, Aiden Xu, Vincent Mendez, Filippo Agnesi, Sandro Iannaccone, Pietro Mortini, Silvestro Micera and Simone Romeni, 20 January 2026, APL Bioengineering.

DOI: 10.1063/5.0297307

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.