AI can spot cancer—but it can also spot who you are, and that turns out to matter.

- A new study finds that artificial intelligence systems used to diagnose cancer from pathology slides do not perform equally for all patients, with accuracy varying across race, gender, and age groups.

- Researchers uncovered three main reasons behind this bias and introduced a new approach that dramatically reduced these performance gaps.

- The results underscore the importance of routinely testing medical AI for bias so these tools can support fair and accurate cancer care for everyone.

How Pathology Guides Cancer Diagnosis

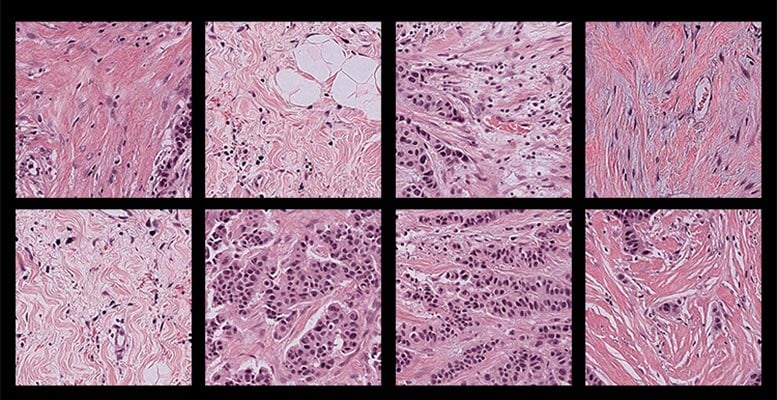

Pathology has long played a central role in how cancer is identified and treated. In this process, a pathologist examines an extremely thin slice of human tissue under a microscope, searching for visual signs that reveal whether cancer is present and, if so, what type and stage it may be.

For a trained expert, viewing a pink, swirling tissue sample dotted with purple cells is much like grading an anonymous test. The slide contains critical information about the disease itself, but it does not reveal personal details about the patient.

When AI Interprets More Than Disease

That assumption does not fully hold for artificial intelligence systems now being used in pathology. A new study led by researchers at Harvard Medical School shows that pathology AI models can extract demographic information directly from tissue slides. This ability can introduce bias into cancer diagnoses across different patient populations.

By examining several widely used AI models designed for cancer detection, the researchers found that performance varied depending on patients’ self-reported gender, race, and age. They also identified multiple reasons why these disparities occur.

To address the problem, the team developed a new framework called FAIR-Path, which significantly reduced bias in the tested models.

“Reading demographics from a pathology slide is thought of as a ‘mission impossible’ for a human pathologist, so the bias in pathology AI was a surprise to us,” said senior author Kun-Hsing Yu, associate professor of biomedical informatics in the Blavatnik Institute at HMS and HMS assistant professor of pathology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Yu emphasized that identifying and correcting bias in medical AI is essential, since it can influence diagnostic accuracy and patient outcomes. The success of FAIR-Path suggests that improving fairness in cancer pathology AI, and potentially other medical AI tools, may be achievable with relatively modest changes.

The work, which was supported in part by federal funding, is described today (December 16) in Cell Reports Medicine.

Testing AI for Diagnostic Bias

Yu and his colleagues evaluated bias in four commonly used pathology AI models under development for cancer diagnosis. These deep-learning systems are trained on large collections of labeled pathology slides, allowing them to learn visual patterns associated with disease and apply that knowledge to new samples.

The team tested the models using a large, multi-institutional dataset that included pathology slides from 20 different cancer types.

Across all four models, the researchers found consistent performance gaps. Diagnostic accuracy was lower for certain groups defined by race, gender, and age. For instance, the models had difficulty distinguishing lung cancer subtypes in African American patients and in male patients. They also struggled with breast cancer subtypes in younger patients and showed reduced detection accuracy for breast, renal, thyroid, and stomach cancers in specific demographic groups. Overall, these disparities appeared in about 29 percent of the diagnostic tasks analyzed.

According to Yu, these errors occur because the models extract demographic information from tissue images and then rely on patterns linked to those demographics when making diagnostic decisions.

The findings were unexpected. “Because we would expect pathology evaluation to be objective,” Yu said. “When evaluating images, we don’t necessarily need to know a patient’s demographics to make a diagnosis.”

This raised a critical question for the research team: Why was pathology AI failing to meet the same standard of objectivity?

Why Bias Emerges in Pathology AI

The researchers identified three main contributors to the problem.

First, training data are often uneven. Samples are easier to obtain from some demographic groups than others, which means AI models are trained on unbalanced datasets. This makes accurate diagnosis more difficult for groups that are underrepresented, including certain populations defined by race, age, or gender.

However, Yu noted that “the problem turned out to be much deeper than that.” In some cases, the models performed worse for particular demographic groups even when sample sizes were similar.

Further analysis pointed to differences in disease incidence. Some cancers occur more frequently in certain populations, allowing AI models to become more accurate for those groups. As a result, the same models may struggle when diagnosing cancers in populations where those diseases are less common.

The models also appear to detect subtle molecular differences across demographic groups. For example, they may identify mutations in cancer driver genes and use those signals as shortcuts for diagnosis. This approach can fail in populations where those mutations occur less frequently.

“We found that because AI is so powerful, it can differentiate many obscure biological signals that cannot be detected by standard human evaluation,” Yu said.

Over time, this can lead models to focus on features linked more closely to demographics than to disease itself, reducing accuracy across diverse patient groups.

Taken together, Yu said, these findings show that bias in pathology AI is influenced not only by the quality and balance of training data, but also by how the models are trained to interpret what they see.

Reducing Bias With a Simple Framework

After identifying the sources of bias, the researchers set out to address them.

They created FAIR-Path, a framework based on an existing machine-learning technique known as contrastive learning. This approach teaches AI models to focus more strongly on meaningful differences, such as those between cancer types, while minimizing attention to less relevant distinctions, including demographic characteristics.

When FAIR-Path was applied to the tested models, diagnostic disparities dropped by about 88 percent.

“We show that by making this small adjustment, the models can learn robust features that make them more generalizable and fairer across different populations,” Yu said.

The result is encouraging, he added, because it suggests that meaningful reductions in bias are possible even without perfectly balanced or fully representative training datasets.

Looking ahead, Yu and his colleagues are working with institutions worldwide to study pathology AI bias in regions with different demographics, medical practices, and clinical settings. They are also exploring how FAIR-Path could be adapted for situations with limited data. Another goal is to better understand how AI-driven bias contributes to broader disparities in health care and patient outcomes.

Ultimately, Yu said, the aim is to develop pathology AI tools that support human experts by delivering fast, accurate, and fair diagnoses for all patients.

“I think there’s hope that if we are more aware of and careful about how we design AI systems, we can build models that perform well in every population,” he said.

Reference: “Contrastive Learning Enhances Fairness in Pathology Artificial Intelligence Systems” 16 December 2025, Cell Reports Medicine.

DOI: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2025.102527

Additional authors on the study include Shih-Yen Lin, Pei-Chen Tsai, Fang-Yi Su, Chun-Yen Chen, Fuchen Li, Junhan Zhao, Yuk Yeung Ho, Tsung-Lu Michael Lee, Elizabeth Healey, Po-Jen Lin, Ting-Wan Kao, Dmytro Vremenko, Thomas Roetzer-Pejrimovsky, Lynette Sholl, Deborah Dillon, Nancy U. Lin, David Meredith, Keith L. Ligon, Ying-Chun Lo, Nipon Chaisuriya, David J. Cook, Adelheid Woehrer, Jeffrey Meyerhardt, Shuji Ogino, MacLean P. Nasrallah, Jeffrey A. Golden, Sabina Signoretti, and Jung-Hsien Chiang.

Funding was provided by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute at the National Institutes of Health (grants R35GM142879, R01HL174679), the Department of Defense (Peer Reviewed Cancer Research Program Career Development Award HT9425-231-0523), the American Cancer Society (Research Scholar Grant RSG-24-1253761-01-ESED), a Google Research Scholar Award, a Harvard Medical School Dean’s Innovation Award, the National Science and Technology Council of Taiwan (grants NSTC 113-2917-I-006-009, 112-2634-F-006-003, 113-2321-B-006-023, 114-2917-I-006-016), and a doctoral student scholarship from the Xin Miao Education Foundation.

Ligon was a consultant of Travera, Bristol Myers Squibb, Servier, IntegraGen, L.E.K. Consulting, and Blaze Bioscience; received equity from Travera; and has research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb and Lilly. Vremenko is a cofounder and shareholder of Vectorly.

The authors prepared the initial manuscript and used ChatGPT to edit selected sections to improve readability. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.