A new lens-free imaging system uses software to see finer details from farther away than optical systems ever could before.

Imaging technology has reshaped how scientists explore the universe – from charting distant galaxies using radio telescope arrays to revealing tiny structures inside living cells. Despite this progress, one major limitation has remained unresolved. Capturing images that are both highly detailed and wide in scope at optical wavelengths has required bulky lenses and extremely precise physical alignment, making many applications difficult or impractical.

Researchers at the University of Connecticut may have found a way around this obstacle. A new study led by Guoan Zheng, a biomedical engineering professor and director of the UConn Center for Biomedical and Bioengineering Innovation (CBBI), along with his team at the University of Connecticut College of Engineering, was published in Nature Communications. The work introduces a new imaging strategy that could significantly expand what optical systems can do in scientific research, medicine, and industrial settings.

Why Synthetic Aperture Imaging Breaks Down at Visible Light

“At the heart of this breakthrough is a longstanding technical problem,” said Zheng. “Synthetic aperture imaging – the method that allowed the Event Horizon Telescope to image a black hole – works by coherently combining measurements from multiple separated sensors to simulate a much larger imaging aperture.”

This approach works well in radio astronomy because radio waves have long wavelengths, which makes precise coordination between sensors achievable. Visible light operates on a much smaller scale. At those wavelengths, the physical accuracy needed to keep multiple sensors synchronized becomes extremely difficult to maintain, placing strict limits on traditional optical synthetic aperture systems.

Letting Software Do the Synchronizing

The Multiscale Aperture Synthesis Imager (MASI) addresses this challenge in a fundamentally different way. Instead of requiring sensors to remain perfectly synchronized during measurement, MASI allows each optical sensor to collect light on its own. Computational algorithms are then used to align and synchronize the data after it has been captured.

Zheng describes the concept as similar to several photographers observing the same scene. Rather than taking standard photographs, each one records raw information about the behavior of light waves. Software later combines these independent measurements into a single image with exceptionally high detail.

This computational approach to phase synchronization removes the need for rigid interferometric setups, which have historically prevented optical synthetic aperture imaging from being widely used in real-world applications.

How MASI Captures and Rebuilds Light

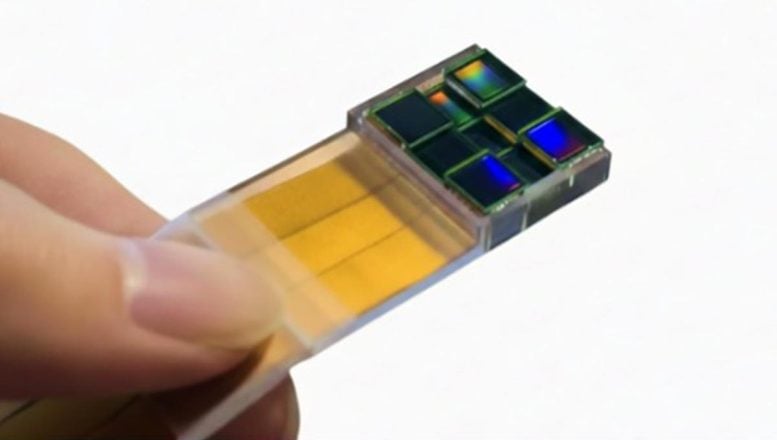

MASI differs from conventional optical systems in two major ways. First, it does not rely on lenses to focus light. Instead, it uses an array of coded sensors placed at different locations within a diffraction plane. Each sensor records diffraction patterns, which describe how light waves spread after interacting with an object. These patterns contain both amplitude and phase information that can later be recovered using computational methods.

After the complex wavefield from each sensor is reconstructed, the system digitally extends the data and mathematically propagates the wavefields back to the object plane. A computational phase synchronization process then adjusts the relative phase differences between sensors. This iterative process increases coherence and concentrates energy in the combined image.

This software-based optimization is the central advance. By aligning data computationally rather than physically, MASI overcomes the diffraction limit and other restrictions that have traditionally governed optical imaging.

A Virtual Aperture With Fine Detail

The final result is a virtual synthetic aperture that is larger than any single sensor. This allows the system to achieve sub-micron resolution while still covering a wide field of view, all without using lenses.

Traditional lenses used in microscopes, cameras, and telescopes force engineers to balance resolution against working distance. To see finer details, lenses usually must be placed very close to the object, sometimes just millimeters away. That requirement can limit access, reduce flexibility, or make certain imaging tasks invasive.

MASI removes this constraint by capturing diffraction patterns from distances measured in centimeters and reconstructing images with sub-micron detail. Zheng compares this to being able to examine the fine ridges of a human hair from across a desk rather than holding it just inches from your eye.

Scalable Applications Across Many Fields

“The potential applications for MASI span multiple fields, from forensic science and medical diagnostics to industrial inspection and remote sensing,” said Zheng, “But what’s most exciting is the scalability – unlike traditional optics that become exponentially more complex as they grow, our system scales linearly, potentially enabling large arrays for applications we haven’t even imagined yet.”

The Multiscale Aperture Synthesis Imager represents a shift in how optical imaging systems can be designed. By separating data collection from synchronization and replacing bulky optical components with software-controlled sensor arrays, MASI shows how computation can overcome long-standing physical limits. The approach opens the door to imaging systems that are highly detailed, adaptable, and capable of scaling to sizes that were previously out of reach.

Reference: “Multiscale aperture synthesis imager” by Ruihai Wang, Qianhao Zhao, Tianbo Wang, Mitchell Modarelli, Peter Vouras, Zikun Ma, Zhixuan Hong, Kazunori Hoshino, David Brady and Guoan Zheng, 26 November 2025, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-65661-8

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.