Researchers have created gyromorphs, a new material that controls light more effectively than any structure used so far in photonic chips.

These hybrid patterns combine order and disorder in a way that stops light from entering from any angle. The discovery solves major limitations found in quasicrystals and other engineered materials. It may open the door to faster, more efficient light-powered computers.

Light-Based Computers and the Need for Better Materials

Researchers are working on computers that use light, or photons, instead of electrical currents to store information and perform calculations. Machines built around light have the potential to run faster and use far less energy than today’s electronics.

One of the biggest obstacles in building these systems—still an emerging technology—is the difficulty of redirecting extremely small light signals inside a chip without reducing their strength. Solving this requires new approaches to materials design. These devices must include a lightweight substance capable of blocking unwanted light arriving from every direction, an ability provided by an “isotropic bandgap material.”

NYU Team Discovers Gyromorphs

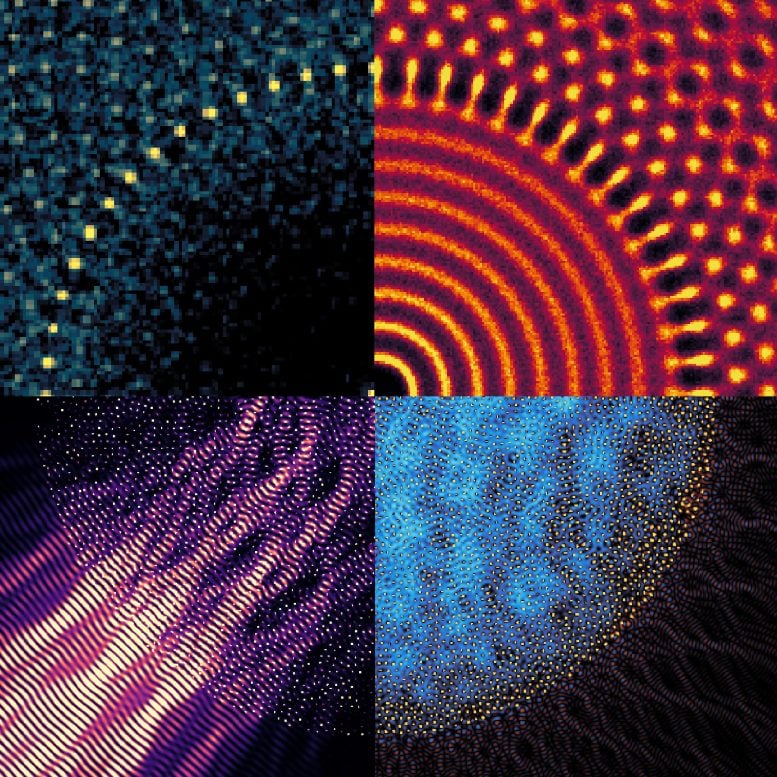

Scientists at New York University have now identified a material called “gyromorphs” that meets this requirement more effectively than any structure studied so far. Gyromorphs combine characteristics of both liquids and crystals and outperform all known materials at preventing light from entering from any angle. Their findings, published in Physical Review Letters, introduce a new strategy for tuning optical behavior and could help move light-based computing forward.

“Gyromorphs are unlike any known structure in that their unique makeup gives rise to better isotropic bandgap materials than is possible with current approaches,” says Stefano Martiniani, an assistant professor of physics, chemistry, mathematics, and neural science, and the paper’s senior author.

Why Quasicrystals Fall Short

When designing isotropic bandgap materials, researchers have often used quasicrystals. These structures were first described by physicists Paul Steinhardt and Dov Levine in the 1980s and observed experimentally by Dan Schechtman, who later received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2011. Quasicrystals follow mathematical rules, yet unlike ordinary crystals, their patterns never repeat.

Despite their unique structure, quasicrystals come with a limitation highlighted by the NYU team. They can either block light entirely, but only from a small set of directions, or weaken light from all directions without fully preventing it. This trade-off has kept scientists searching for better alternatives that can reliably stop light from draining signal strength.

Engineering New Metamaterials

In their Physical Review Letters study, the NYU researchers created “metamaterials,” engineered structures whose behavior depends on their architecture rather than on the chemical nature of their components. The challenge in developing metamaterials lies in understanding how their arrangement produces specific physical effects.

To find workable solutions, the team designed an algorithm that generates disordered but functional structures. Through this effort, they uncovered a new form of “correlated disorder,” which describes materials that fall between fully ordered and fully random systems.

“Think of trees in a forest—they grow at random positions, but not completely random because they’re usually a certain distance from one another,” explains Martiniani. “This new pattern, gyromorphs, combines properties that we believed to be incompatible and displays a function that outperforms all ordered alternatives, including quasicrystals.”

How Gyromorphs Achieve Complete Light Blocking

During their analysis, the researchers found that every isotropic bandgap material shared a specific structural signature.

“We wanted to make this structural signature as pronounced as possible,” adds Mathias Casiulis, a postdoctoral fellow in NYU’s Department of Physics and the paper’s lead author. “The result was a new class of materials—gyromorphs—that reconcile seemingly incompatible features.

“This is because gyromorphs don’t have a fixed, repeating structure like a crystal, which gives them a liquid-like disorder, but, at the same time, if you look at them from a distance they form regular patterns. These properties work together to create bandgaps that lightwaves can’t penetrate from any direction.”

Reference: “Gyromorphs: A New Class of Functional Disordered Materials” by Mathias Casiulis, Aaron Shih and Stefano Martiniani, 6 November 2025, Physical Review Letters.

DOI: 10.1103/gqrx-7mn2

The research also included Aaron Shih, an NYU graduate student, and was supported, in part, by the Simons Center for Computational Physical Chemistry (839534) and by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (FA9550-25-1-0359).

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.