A new way of capturing light from atoms could finally unlock ultra-powerful, million-qubit quantum computers.

After decades of effort, researchers may finally be closing in on a practical path toward powerful quantum computers. These machines are expected to handle certain calculations so efficiently that tasks taking classical computers thousands of years could be completed in just hours.

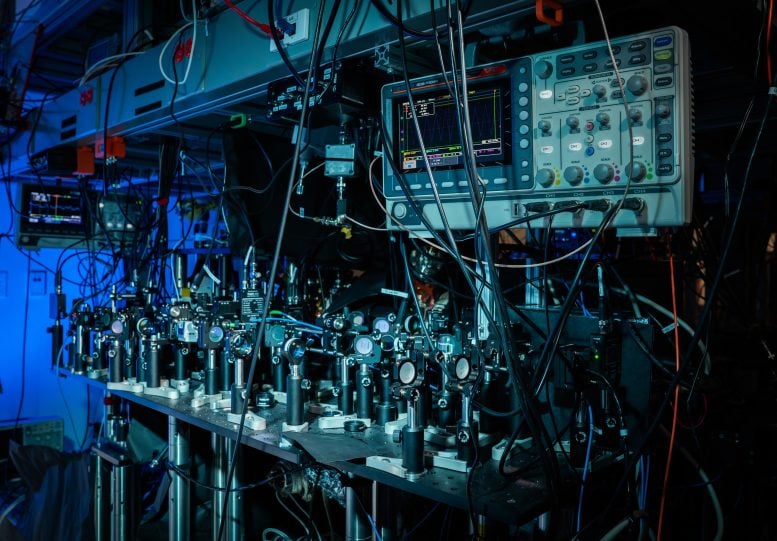

A research team led by physicists at Stanford University has created a new type of optical cavity designed to capture single photons, the smallest units of light, emitted by individual atoms. Those atoms store qubits, which are the basic units of information in a quantum computer. For the first time, this system allows information to be read from all qubits at the same time rather than one by one.

Capturing Light From Individual Atoms

In a study published in Nature, the researchers describe a working array of 40 optical cavities, each holding a single atom qubit, along with a larger prototype containing more than 500 cavities. The results suggest a realistic path toward building quantum networks with as many as one million qubits.

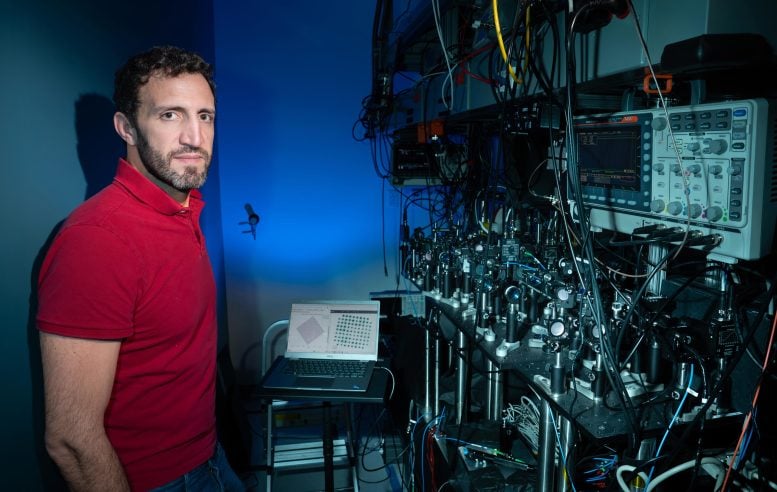

“If we want to make a quantum computer, we need to be able to read informati on out of the quantum bits very quickly,” said Jon Simon, the study’s senior author and associate professor of physics and of applied physics in Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences. “Until now, there hasn’t been a practical way to do that at scale because atoms just don’t emit light fast enough, and on top of that, they spew it out in all directions. An optical cavity can efficiently guide emitted light toward a particular direction, and now we’ve found a way to equip each atom in a quantum computer within its own individual cavity.”

How Optical Cavities Work

An optical cavity forms when light reflects repeatedly between two or more surfaces. The effect is similar to standing between mirrors in a fun house and seeing reflections multiply into the distance. In scientific applications, these structures are far smaller and are used to make light interact more strongly with atoms by forcing it to pass through the same space many times.

Scientists have studied optical cavities for decades, but working with atoms presents a challenge because they are extremely small and nearly transparent. Getting enough light to interact with them efficiently has proven difficult.

A New Cavity Design Using Microlenses

Instead of relying on many light reflections, the Stanford team took a different approach. They placed microlenses inside each cavity to focus light tightly onto a single atom. Although this method involves fewer reflections, it turns out to be more effective for extracting quantum information.

“We have developed a new type of cavity architecture; it’s not just two mirrors anymore,” said Adam Shaw, a Stanford Science Fellow and first author on the study. “We hope this will enable us to build dramatically faster, distributed quantum computers that can talk to each other with much faster data rates.”

Why Qubits Are So Powerful

Traditional computers process information using bits that are either zero or one. Quantum computers operate differently, using qubits that can exist as zero, one, or both states at the same time. This unique behavior allows quantum systems to evaluate many possible solutions simultaneously.

“A classical computer has to churn through possibilities one by one, looking for the correct answer,” said Simon. “But a quantum computer acts like noise-canceling headphones that compare combinations of answers, amplifying the right ones while muffling the wrong ones.”

Scaling Toward Quantum Supercomputers

Experts believe that quantum computers will need millions of qubits to outperform today’s most powerful supercomputers. Achieving that scale will likely require connecting many smaller quantum computers into larger networks. The cavity system demonstrated in this research offers a highly efficient way to read qubits in parallel, which is essential for building systems of that size.

In addition to the 40-cavity setup described in the paper, the team has already tested a proof-of-concept array with more than 500 cavities and is working toward systems with tens of thousands. Their long-term vision includes quantum data centers where individual machines are linked together through cavity-based network interfaces.

Broad Implications Beyond Computing

Significant engineering challenges remain, but the researchers believe the potential impact is enormous. Scaled quantum computers could accelerate advances in materials science and chemical synthesis, including applications relevant to drug discovery, as well as dramatically improve code-breaking capabilities.

The ability to efficiently collect light at the single-particle level could also benefit fields beyond computing. Applications may include advanced biosensing, improved microscopy, and even astronomy. Quantum networks could one day allow optical telescopes to achieve resolutions high enough to directly observe planets orbiting stars outside our solar system.

“As we understand more about how to manipulate light at a single particle level, I think it will transform our ability to see the world,” Shaw said.

Reference: “A cavity-array microscope for parallel single-atom interfacing” 28 January 2026, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-10035-9

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.