A new electronic eye implant has restored reading vision to people blinded by dry age-related macular degeneration.

In a major trial, patients using the PRIMA implant and augmented-reality glasses were able to see letters and words again after years of darkness.

Groundbreaking Electronic Eye Restores Reading Vision

People who had lost their sight have regained the ability to read after receiving a groundbreaking electronic eye implant combined with augmented-reality glasses, according to a clinical trial led by researchers from UCL and Moorfields Eye Hospital.

Findings from the European study, published in The New England Journal of Medicine, revealed that 84% of participants were able to recognize letters, numbers, and words using prosthetic vision in an eye that had previously gone blind. Their vision loss was caused by an advanced, untreatable form of dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD) known as geographic atrophy.

On average, participants treated with the implant were able to read five lines of a standard vision chart. Before the procedure, some could not see the chart at all.

The clinical trial involved 38 participants across 17 hospitals in five European countries, with Moorfields Eye Hospital serving as the only UK site. The study tested a cutting-edge retinal implant called PRIMA. Every patient selected for the procedure had completely lost central vision in one eye prior to implantation.

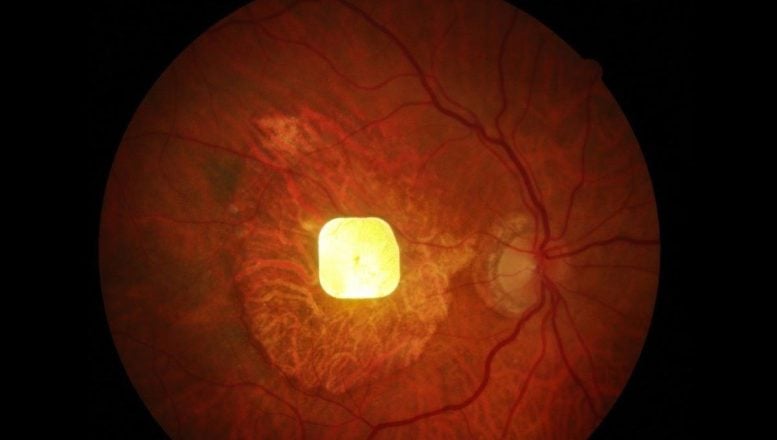

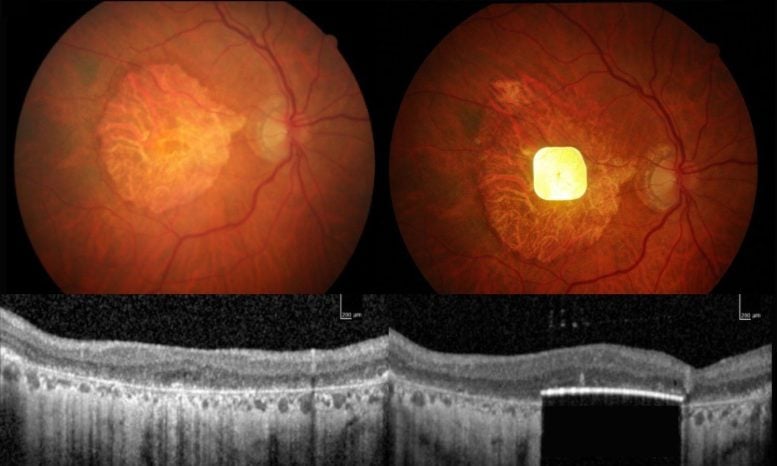

Dry AMD is a gradual condition that damages the macula, the part of the retina responsible for sharp central vision. Over time, the light-sensitive retinal cells deteriorate and die, leading to blurring and eventual blindness. In the late stage of the disease, known as geographic atrophy (GA), the central macula breaks down entirely. GA affects an estimated 5 million people worldwide and currently has no approved treatment. All patients in this trial had lost central vision in the affected eye, leaving only limited peripheral sight.

A New Era in Artificial Vision

The PRIMA implant represents the first successful device capable of restoring the ability to read through an eye that had lost vision.

Mr. Mahi Muqit, associate professor at the UCL Institute of Ophthalmology and senior vitreoretinal consultant at Moorfields Eye Hospital, led the UK arm of the study. He said: “In the history of artificial vision, this represents a new era. Blind patients are actually able to have meaningful central vision restoration, which has never been done before.

“Getting back the ability to read is a major improvement in their quality of life, lifts their mood and helps to restore their confidence and independence. The PRIMA chip operation can safely be performed by any trained vitreoretinal surgeon in under two hours – that is key for allowing all blind patients to have access to this new medical therapy for GA in dry AMD.”

The surgical procedure involves a vitrectomy, in which the eye’s natural gel is removed from between the lens and the retina. The surgeon then inserts a wafer-thin microchip, about the size of a SIM card (2mm x 2mm), beneath the central retina through a small opening.

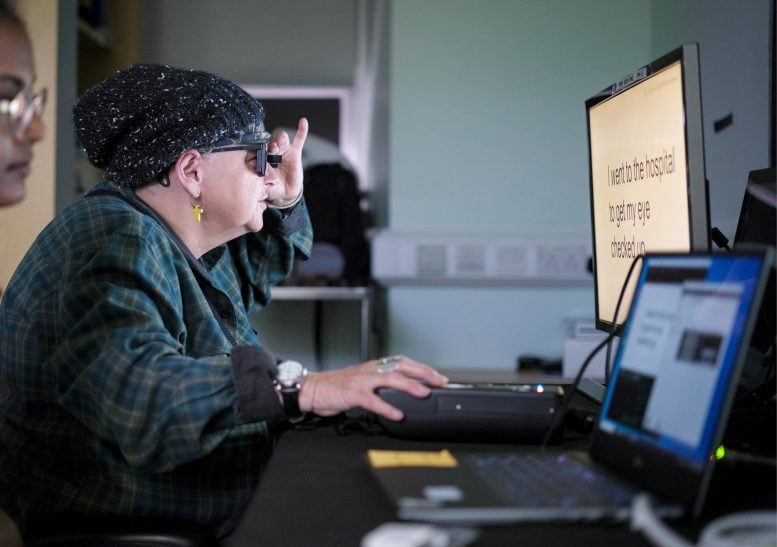

After surgery, the patient wears augmented-reality glasses equipped with a video camera connected to a small computer with a zoom function, worn on the waistband. The camera captures visual information and transmits it to the implant, allowing the brain to interpret these signals as vision.

Reconnecting the Brain to Vision Through AI

Around a month or so after the operation, once the eye has settled, the new chip is activated. The video camera in the glasses projects the visual scene as an infrared beam directly across the chip to activate the device. Artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms through the pocket computer process this information, which is then converted into an electrical signal. This signal passes through the retinal and optical nerve cells into the brain, where it is interpreted as vision. The patient uses their glasses to focus and scan across the main object in the projected image from the video camera, using the zoom feature to enlarge the text. Each patient goes through an intensive rehabilitation program over several months to learn to interpret these signals and start reading again.

No significant decline in existing peripheral vision was observed in trial participants.

These findings pave the way for seeking approval to market this new device.

Personal Story: Sheila Irvine’s Return to Reading

Sheila Irvine, one of Moorfields’ patients on the trial who was diagnosed with age-related macular degeneration, said: “I wanted to take part in research to help future generations, and my optician suggested I get in touch with Moorfields. Before receiving the implant, it was like having two black discs in my eyes, with the outside distorted.

“I was an avid bookworm, and I wanted that back. I was nervous, excited, all those things. There was no pain during the operation, but you’re still aware of what’s happening. It’s a new way of looking through your eyes, and it was dead exciting when I began seeing a letter. It’s not simple, learning to read again, but the more hours I put in, the more I pick up.

“The team at Moorfields has given me challenges, like ‘Look at your prescription’, which is always tiny. I like stretching myself, trying to look at the little writing on tins, doing crosswords.

“It’s made a big difference. Reading takes you into another world. I’m definitely more optimistic now.”

The global trial was led by Dr. Frank Holz of the University of Bonn, with participants from the UK, France, Italy, and the Netherlands.

The PRIMA System device used in this operation is being developed by Science Corporation (science.xyz), which develops brain-computer interfaces and neural engineering.

Mr. Muqit added: “My feeling is that the door is open for medical devices in this area, because there is no treatment currently licensed for dry AMD – it doesn’t exist.

“I think it’s something that, in the future, could be used to treat multiple eye conditions.”

Inside the PRIMA System: A Solar-Powered Retinal Chip

The device is a novel wireless subretinal photovoltaic implant paired with specialized glasses that project near-infrared light to the implant, which acts like a miniature solar panel.

It is 30 micrometers/microns (0.03mm) thick, about half the thickness of a human hair.

A zoom feature gives patients the ability to magnify letters. It is implanted in the subretinal layer, under the retinal cells that have died. Until the glasses and waistband computer are turned on, the implant has no visual stimulus or signal to pass through to the brain.

In addition to practicing their reading and attending regular training, patients on the trial were encouraged to explore ways of using the device. Sheila chose to learn to do puzzles and crosswords while one of the French patients used them to help navigate the Paris Metro – both tasks being more complex than reading alone.

Reference: “Subretinal Photovoltaic Implant to Restore Vision in Geographic Atrophy Due to AMD” by Frank G. Holz, Yannick Le Mer, Mahiul M.K. Muqit, Lars-Olof Hattenbach, Andrea Cusumano, Salvatore Grisanti, Laurent Kodjikian, Marco Andrea Pileri, Frederic Matonti, Eric Souied, Boris V. Stanzel, Peter Szurman, Michel Weber, Karl Ulrich Bartz-Schmidt, Nicole Eter, Marie Noelle Delyfer, Jean François Girmens, Koen A. van Overdam, Armin Wolf, Ralf Hornig, Martina Corazzol, Frank Brodie, Lisa Olmos de Koo, Daniel Palanker and José-Alain Sahel, 19 October 2025, New England Journal of Medicine.

DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2501396

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google, Discover, and News.