A new study shows that promising single-crystal battery materials degrade for reasons scientists hadn’t fully recognized before.

Scientists at Argonne National Laboratory and the UChicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (UChicago PME) have identified the source of a long-standing problem in battery performance that has been linked to fading capacity, reduced lifespan, and, in rare cases, safety hazards such as fire.

Reporting their findings in Nature Nanotechnology

“Electrification of society needs everyone’s contribution,” said one of the corresponding authors Khalil Amine, Argonne Distinguished Fellow and Joint Professor at UChicago, “If people don’t trust batteries to be safe and long-lasting, they won’t choose to use them.”

Traditional lithium-ion batteries that rely on polycrystalline Ni-rich materials (PC-NMC) in their cathodes have long been known to suffer from cracking. To address this, many researchers recently shifted their attention to single-crystal Ni-rich layered oxides (SC-NMC). However, these newer materials have not consistently delivered the expected improvements in durability or performance.

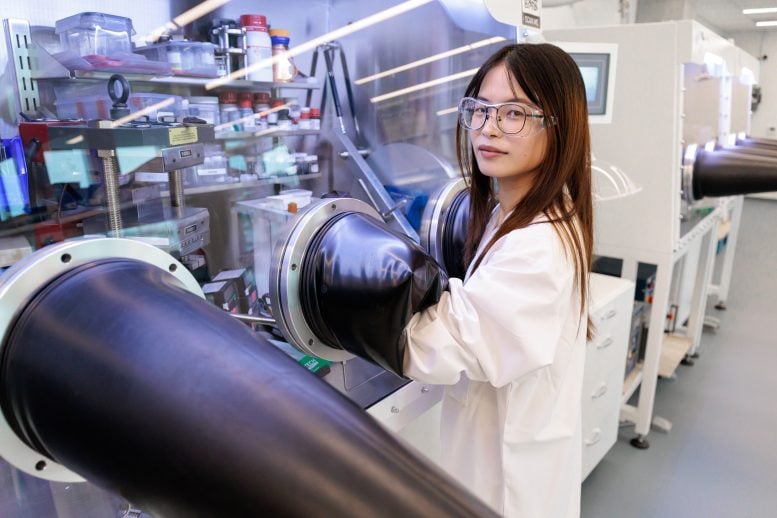

The new study, led by first author Jing Wang during her PhD work at UChicago PME through the GRC program and supervised by Prof. Shirley Meng’s Laboratory for Energy Storage and Conversion alongside Amine’s Advanced Battery Technology team, pinpointed why. The researchers found that design rules developed for polycrystalline cathodes were being applied to single-crystal materials, even though the two behave differently under operating conditions.

Through the GRC program and UChicago’s Energy Transition Network, Wang was able to work closely with National Lab Scientist and Industry partners to proceed the world-changing engineering projects.

“When people try to transition to single-crystal cathodes, they have been following similar design principles as the polycrystal ones,” said Wang, now a postdoctoral researcher working with UChicago and Argonne. “Our work identifies that the major degradation mechanism of the single-crystal particles is different from the polycrystal ones, which leads to the different composition requirements.”

The study not only challenged conventional design, but also the materials used, redefining the roles of cobalt and manganese in batteries’ mechanical failure.

“Not only are new design strategies needed, different materials will also be required to help single-crystal cathode batteries reach their full potential,” said Meng, who is also the director of the Energy Storage Research Alliance (ESRA) based at Argonne. “By better understanding how different types of cathode materials degrade, we can help design a suite of high-functioning cathode materials for the world’s energy needs.”

A cracking mystery

As a polycrystal cathode battery charges and discharges, the tiny, stacked primary particles swell and shrink. This repeated expansion and contraction can widen the grain boundaries that separate the polycrystals, similar to how repeated freezing and thawing puts potholes in city streets.

“Typically, it will suffer about five to 10% volume expansion or shrinkages,” Wang said. “Once an expansion or shrinkage exceeds the elastic limits, it will lead to the particle cracking.”

If the cracks widen too much, electrolyte can get in, which can lead to lead to unwanted side reactions and oxygen release that can raise safety concerns, including the risk of thermal runaway. But, barring those dramatic circumstances, a more day-to-day effect is capacity degradation – the batteries fade over time, increasingly incapable of delivering the same charge they did when they were new.

Since they’re not made of many stacked crystals, single-crystal cathode materials don’t have those starting grain boundaries. But they were still degrading.

The new UChicago PME-Argonne research showed that switching the materials wasn’t as simple as swapping out a new part.

“We demonstrate that degradation in single-crystal NMC cathodes is predominantly governed by a distinct mechanical failure mode,” said another corresponding author, Tongchao Liu, a chemist at Argonne. “By identifying this previously underappreciated mechanism, this work establishes a direct link between material composition and degradation pathways, providing deeper insight into the origins of performance decay in these materials.”

Using multi-scale synchrotron X ray techniques and high-resolution transmission electron microscope, they discovered that cracking in single-crystal cathodes is primarily driven by reaction heterogeneity. Particles were undergoing reactions at different rates, causing strain not between many crystals as with polycrystal designs, but within one.

Different solutions

Polycrystal cathodes are a balancing act of nickel, manganese, and cobalt. Cobalt actually causes cracking, but was needed to mitigate a separate problem called Li/Ni disorder.

By building and testing one nickel-cobalt battery (no manganese) and one nickel-manganese battery (no cobalt), the team found that, for single-crystal cathodes, the opposite was true. Manganese was more mechanically detrimental than cobalt and cobalt actually helped batteries last longer.

Cobalt, however, is more expensive than nickel or manganese. Wang said the team’s next step to turning this lab innovation into a real-world product is finding less-expensive materials that replicate cobalt’s good results.

“Advances come in cycles,” Amine said. “You solve a problem, then move on to the next. The insights outlined in this collaborative paper will help future researchers at Argonne, UChicago PME, and elsewhere create safer, longer-lasting materials for tomorrow’s batteries.”

Reference: “Nanoscopic strain evolution in single-crystal battery positive electrodes” by Jing Wang, Tongchao Liu, Weiyuan Huang, Lei Yu, Haozhe Zhang, Tao Zhou, Tianyi Li, Xiaojing Huang, Xianghui Xiao, Lu Ma, Martin V. Holt, Kun Ryu, Rachid Amine, Wenqian Xu, Luxi Li, Jianguo Wen, Ying Shirley Meng and Khalil Amine, 16 December 2025, Nature Nanotechnology.

DOI: 10.1038/s41565-025-02079-9

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.