By adjusting a simple chemical ratio, scientists discovered a new way to control exotic quantum states that could underpin the next generation of quantum computers.

Even supercomputers can stall out on problems where nature refuses to play by everyday rules. Predicting how complex molecules behave or testing the strength of modern encryption can demand calculations that grow too quickly for classical hardware to keep up. Quantum computers are designed to tackle that kind of complexity, but only if engineers can build systems that run with extremely low error rates.

One of the most promising routes to that reliability involves a rare class of materials called topological superconductors. In plain terms, these are superconductors that also have built-in “protected” quantum behavior, which researchers hope could help shield delicate quantum information from noise. The catch is that making materials with these properties is famously difficult.

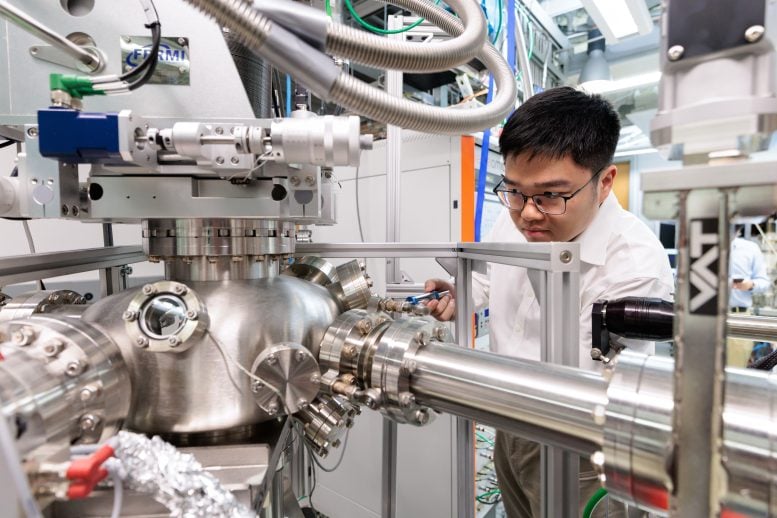

A team from the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (UChicago PME) and West Virginia University reports a simpler way to coax those exotic properties into a real material. Instead of relying on elaborate fabrication tricks, they show that a small change in chemistry can reshape how large groups of electrons interact, which can determine whether the material enters an ordinary state or something far more unusual.

Their method centers on growing ultrathin films and carefully adjusting the balance between tellurium and selenium. That single compositional change turned out to be enough to push the material through multiple quantum phases, including a sought-after topological superconducting state.

The results, published in Nature Communications, point to electron correlations as the key lever. Correlations describe how strongly electrons affect one another, and in quantum materials that collective behavior can decide what phase emerges. In this system, the tellurium to selenium ratio acts like a practical tuning control for dialing those correlations up or down until the desired regime appears.

“We can tune this correlation effect like a dial,” said Haoran Lin, a UChicago PME graduate student and first author of the new work. “If the correlations are too strong, electrons get frozen in place. If they’re too weak, the material loses its special topological properties. But at just the right level, you get a topological superconductor.”

“This opens up a new direction for quantum materials research,” said Shuolong Yang, Assistant Professor of Molecular Engineering and senior author of the new work. “We’ve developed a powerful tool for designing the kind of materials that next-generation quantum computers will need.”

A tale of two transitions

Iron telluride selenide is a material discovered relatively recently and is known for combining superconductivity with unusual topological behavior.

“This is a unique material because it brings together all the essential ingredients one would hope for in a platform for topological superconductivity: superconductivity itself, strong spin–orbit coupling, and pronounced electronic correlations,” said Subhasish Mandal, an assistant professor of physics at West Virginia University and an author on the new paper. “This combination makes it an ideal system in which to explore how different quantum effects interact and compete.”

In the past, researchers have grown bulk crystals of the material and observed unusual quantum states, but bulk crystals are difficult to work with, and their composition can vary from spot to spot.

Engineering quantum devices

Topological superconductors are promising for building quantum devices of the future—their topological states are inherently stable and resistant to the noise that affects most quantum materials.

Compared to other topological superconductor candidates, the thin films of iron telluride selenide studied by Yang’s team offer several benefits for these applications. They work at higher temperatures than some competing platforms—up to 13 Kelvin compared to around 1 Kelvin for aluminum-based systems, making them easier to cool with standard liquid helium. The thin-film format is also easier to control than bulk crystals and ready for use in device fabrication.

“If you’re trying to use this material for a real application, you need to be able to grow it in a thin film instead of trying to exfoliate layers off of a rock that might not have a consistent composition throughout,” explained Lin.

Multiple research groups are already collaborating with Yang’s team to pattern the films and fabricate quantum devices. The scientists are also continuing to characterize other properties of the thin-film iron telluride selenide.

Reference: “A topological superconductor tuned by electronic correlations” by Haoran Lin, Christopher L. Jacobs, Chenhui Yan, Gillian M. Nolan, Gabriele Berruto, Patrick Singleton, Khanh Duy Nguyen, Yunhe Bai, Qiang Gao, Xianxin Wu, Chao-Xing Liu, Gangbin Yan, Suin Choi, Chong Liu, Nathan P. Guisinger, Pinshane Y. Huang, Subhasish Mandal and Shuolong Yang, 26 December 2025, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-67957-1

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.